Make Frida Great Again

In order to analyse binaries on e.g. Android systems, one is offered a plethora of tools to use to figure out what a binary is doing, whether it is malicious or just buggy. One way to figure out the behaviour of a binary is to utilise the strength of dynamic analysis. Under linux, i.e. Android in particular, Frida is a tool that is used for automated instrumentation of binaries, to inspect memory, function calls etc.

In this blog post, I will describe how to overcome a main issue of Frida such that Frida is applicable to a broader set of binaries. For that I will give in-depth explanations on the different techniques being used to solve the issue. Also I will showcase the use of a python library that emerged as a result of this issue.

Stumbling Frida - The Issue

Frida internally uses the ptrace

- syscall to attach to running processes. Notice that using ptrace requires the CAP_SYS_PTRACE - capability, which is a requirement for tracing arbitrary processes. Thus, an unprivileged user cannot trace e.g. a privileged process. An example is tracing a process on an Android device. If this device is not rooted, then it will not be possible to use ptrace on arbitrary processes.

Lets assume that a user is capable of using ptrace and that user wants to analyse a potentially malicious binary that employs anti-debugging techniques like the following one

if (ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, 0, 0, 0) == -1) {

// traced: nice behaviour

} else {

// not traced: evil behaviour

}

Then Frida can again not be used to analyse all functionality of the process. This is due to the fact that for each tracee there may at most be one tracer.

Frida Gadget

Of course the developers of Frida are well aware of this issue. Therefore they provide a shared object file called frida-gadget.so (downloaded here ), which is to be injected manually into the target process. There are different kinds of interaction types that specify how the connection between the frida server and the frida client is set up.

In the following you can see an example of how to use frida-gadget.so with its default interaction type listen. First, for the target binary:

LD_PRELOAD=/path/to/frida-gadget.so /path/to/target

Now, in order to e.g. trace syscalls that start with “read”:

frida-trace -H 127.0.0.1:27042 -n "Gadget" -i "read*"

- -H 127.0.0.1:27042: Specifies the frida server to connect to. In this case the server is located on localhost on the default port 27042.

- -n “Gadget”: Name of the process to attach to. In this setting, the name of the target process will always be “Gadget”!

- -i “read*”: Specifies what function(s) to trace.

Using LD_PRELOAD is not practical in all cases as e.g. it cannot be used to instrument an SUID - binary. For a more general solution, we need another approach.

ELF - based Injection

The approach used to make a process load frida-gadget.so at startup is ELF - based injection. In order to support as many platforms as possible, those injection techniques will be based on System V gABI . It describes the abstract structure of an ELF - file, occasionally leaving out details to be specified by a corresponding Processor Supplement (e.g. ARM64 or AMD64 ).

Unfortunately, it is not possible to fully implement ELF - based injection without using architecture - or OS - dependent information. Thus, the following platform-specific assumptions were made when designing the techniques:

- ELF - binary is run on ARM64 and Android: This must currently be ensured, because adjusting virtual addresses and file offsets in the binary enforces patching Relocation Tables , which are highly platform - dependent.

- There are no other platform - specific tags for .dynamic - entries other than

- DT_VERSYM

- DT_VERDEF

- DT_VERNEED

- One of the parsers (see Rule of Two ) is build for AMD64 only. Thus the python library will only work on AMD64. Technically, one can try to make sense of the makefiles and change the compilation such that it supports other architectures aswell.

ELF - based injection can be split into two (or more) steps:

- Code injection: Insert code into binary, i.e. make it available for internal structures.

- Code execution: Make injected code executable, i.e. manipulate structures like entry point such that the injected code will be part of the control flow.

There is one special technique that cannot be split into two parts: .dynamic - based injection.

Rule of Two

The techniques to be explained are implemented in a python library , which mainly uses LIEF . LIEF is a binary parser that among other things supports parsing and manipulating ELF - files. However there is a problem with LIEF, i.e. LIEF desperately tries to keep the binary intact. For that LIEF inserts new memory, shuffles segments around and maybe more when just opening and closing the binary. E.g.

binary = lief.parse('/bin/ls')

binary.write('./tmp')

will “build” the binary, i.e. internally calling

builder = lief.ELF.Builder(binary)

builder.build()

which will insert memory (out of nowhere). One could make the hypothesis that LIEF wants to “prepare” the binary for future manipulation and thus already allocates enough space to support e.g. quick PHT injections.

Also LIEF does not provide all necessary functionality to implement the techniques described in this post. E.g. LIEF does not support overwriting a PHT - entry without modifying the linked memory.

To that end, a custom parser is utilised. It supports all necessary functionality that LIEF is lacking or not willing to provide, because it might break correctness. The custom parser, rawelf_injection, takes the name of a binary as an input and performs the requested operations.

An issue is that when calling rawelf_injection, LIEF needs to store the current state of the binary to a temporary file and reparse that file after rawelf_injection is done. This will result in references to objects, that are related to the state of a LIEF - binary before storing the binary to a file, being invalid after LIEF reparsed the binary.

Other problems emerging from using two parsers at the same time will be mentioned throughout the following sections.

Code Injection

Inserting code into the binary can be as easy as just overwriting existing code in .text and as hard as inserting a new segment and a corresponding PHT - entry. Interestingly, not all of the following techniques are applicable in a fixed setting, thus the user of ElfInjection has to know what he/she is doing when performing code injection.

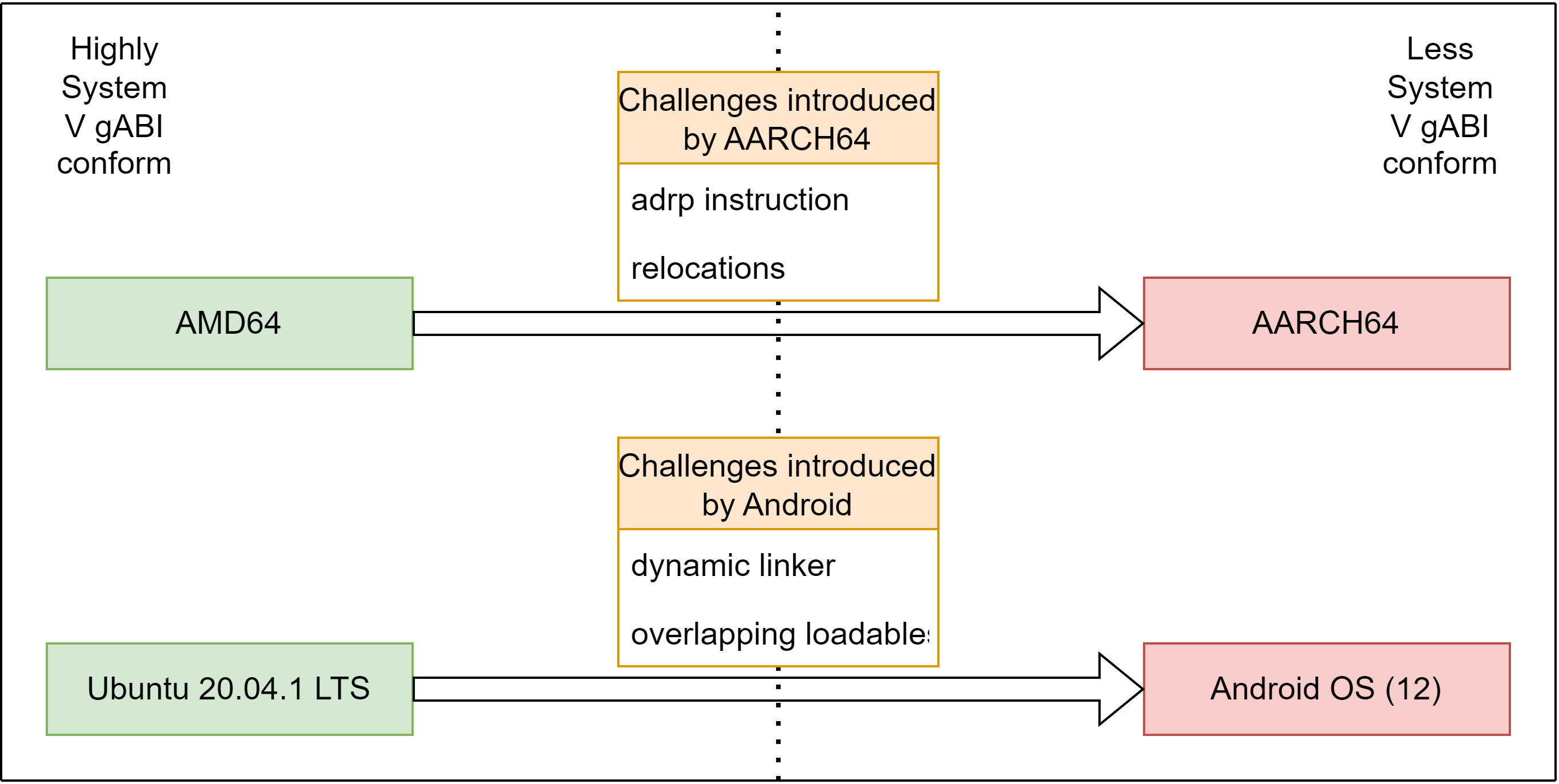

As rawelf_injection has been designed w.r.t. the System V gABI, applying it to ELF - files constructed for Android on AARCH64 was assumed to work just out-of-the-box (except for relocations). rawelf_injection has only been tested on Ubuntu 20.04 LTS on AMD64 up to the date I started applying the techniques to ELF - files run on an Android emulator. Lets first look at an overview of the challenges I experienced before diving into the details:

Unfortunately, it turns out that rawelf_injection does not support platform - independent injection techniques, as OS vendors apparently are allowed to deviate partially from the System V gABI. On the other hand, for different architectures, there are different CPU instructions, like e.g. adrp, that introduce unwanted side effects when inserting new memory.

So lets list the challenges and then try to solve them:

- Inserting new memory into a binary can invalidate cross - references (e.g.

adrp). - Loadable segments should not overlap (see linker_phdr.cpp ; user has to ensure that loadables do not overlap)

- Platform - specific ELF patches (adjust

rawelf_injectionto AARCH64 processor supplement) - Dynamic linker (see .dynsym - based injection for details)

Problem with adrp

Lets assume we want to inject code into an ARM64 - PIE on Android (API level 31, Pixel 3). Then, using NDK r23b’s toolchain (i.e. ndk-build) to compile the program

#include <stdio.h>

ìnt main() {

puts("Hello World!\n");

return 0;

}

there will be at least one .plt - entry that handles all calls to puts. The corresponding .plt - stub may look like this:

$ aarch64-linux-gnu-objdump -j .plt -d hello

...

00000000000006a0 <__libc_init@plt-0x20>:

6a0: a9bf7bf0 stp x16, x30, [sp, #-16]!

6a4: b0000010 adrp x16, 1000 <puts@plt+0x920>

6a8: f944a211 ldr x17, [x16, #2368]

6ac: 91250210 add x16, x16, #0x940

6b0: d61f0220 br x17

...

00000000000006e0 <puts@plt>:

6e0: b0000010 adrp x16, 1000 <puts@plt+0x920>

6e4: f944ae11 ldr x17, [x16, #2392]

6e8: 91256210 add x16, x16, #0x958

6ec: d61f0220 br x17

Notice that adrp will first compute 0x6e0 + 0x1000 and then zero out the least-significant 12 bits (related to page size). Thus x16 will contain 0x1000. Then x17 will contain the value located at address 0x1000 + 0x958 (i.e. 0x958 = 2392), which is the second to last .got.plt - entry, containing the address of the dynamic linker stub (see address 0x6a0 in objdump - output):

$ readelf --wide --sections hello

[Nr] Name Type Address Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

...

[22] .got.plt PROGBITS 0000000000001930 000930 000030 00 WA 0 0 8

...

$ readelf --wide --hex-dump=22 hello

...

0x00001950 a0060000 00000000 a0060000 00000000 ................

Inserting data into the binary can now result in broken references. Lets consider the example that we want to append a new PHT - entry to PHT. Assuming the above platform and build, the PHT is located at

$ readelf --wide --segments hello

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

...

PHDR 0x000040 0x0000000000000040 0x0000000000000040 0x000230 0x000230 R 0x8

...

Appending the PHT - entry will increase the PHDR’s size by 0x38, which again will shift everything located after the PHT by 0x38 to the back. Lets consider .plt again

00000000000006e0 <puts@plt>:

6e0 + 0x38: b0000010 adrp x16, 1000 --> x16 = 0x1000

6e4 + 0x38: f944ae11 ldr x17, [x16, #2392] --> x17 = 0x1000 + 0x958 = 0x1958

6e8 + 0x38: 91256210 add x16, x16, #0x958 --> x16 = 0x1958

6ec + 0x38: d61f0220 br x17

So we will still jump to the same .plt - stub we would jump to, if we did not insert the PHT - entry. In (almost) all cases, this will give you SIGSEG or SIGILL. This is a problem to consider whenever new data is injected into a binary. Despite the fact that we have to take care of unpatchable references, there are also patchable references that can be changed automatically (i.e. using heuristics and math) like e.g. .dynamic entries of tag DT_SYMTAB.

In addition to that, if we assumed that we inserted a loadable segment, i.e. a PHT - entry of type PT_LOAD, then the binary might crash with high probability (for me it crashed on every test). Regarding the kernel

, loadable segments are allowed to overlap, which coincides with System V gABI

(notice the absense of any constraints for segments in comparison to the constraints enforced for sections

). This may lead to the conclusion that either inserting an overlapping loadable segment introduces the same errors regarding adrp as described above, or the dynamic linker contains code that sends a SIGSEG or SIGILL based on a certain condition. As all of the techniques are tested on an Android emulator with the above platform specifications, it could also be that the translator does not like overlapping loadables (/system/bin/ndk_translation_program_runner_binfmt_misc_arm64 is definitely capable of triggering SIGILL!).

Code Cave - based Injection

The first technique described is code injection that relies on finding unused memory between two loadable segments, i.e. segments of type PT_LOAD. For this technique to work properly, we need to consider the following things:

- This is a segment - based approach, which means that code caves must lie between two loadable segments. Thus a code cave cannot be part of the process image.

- Assuming we found a code cave, in order to put it into the process image we need to either create a new or overwrite an existing PHT - entry such that it points to the code cave. Or we need to expand one of the surrounding loadable segments. The latter is hard, because loadable segments may theoretically contain other loadable segments. Therefore only “top - level” loadable segments are used to search for code caves.

- Segment - based code caves need to be searched for with respect to the file offsets and file sizes of the “top - level” loadable segments, because the code injection takes place in the file on disk, not at runtime. Again there is a problem, because the size of a segment on disk

p_fileszmay be strictly less than the size in the process imagep_memsz. Appending a code cave to a loadable segment withp_filesz < p_memszmay result in the injected code being overwritten by the application. Also, if combined with a PHT - based injection, one can set the virtual address and memory size to another code cave in process image. - System V gABI

states that PHT - entries of loadable segments must be sorted ascendingly wrt. their virtual addresses. Therefore the combination of a code cave with overwriting/creating PHT - entries is further limited to the order of PHT - entries. In practice it seems that we can derive from the kernel code

that only the first loadable segment needs to have the smallest virtual address s.t.

load_biasis correctly set (see also the dynamic linker code responsible for calculating theload_biasfor ELF - files loaded by the kernel). There seem to be no checks regarding the order of loadable segments as regards their virtual addresses.

Notice that inserting a PHT - entry to point to the code cave will cause all the problems described in Code Injection .

Injecting code into segment - based code caves is a simple and often stable way to get a binary to execute custom code. Of course seeking code caves can among other things involve analysing control flow to detect “dead” code in e.g. .text that can be overwritten.

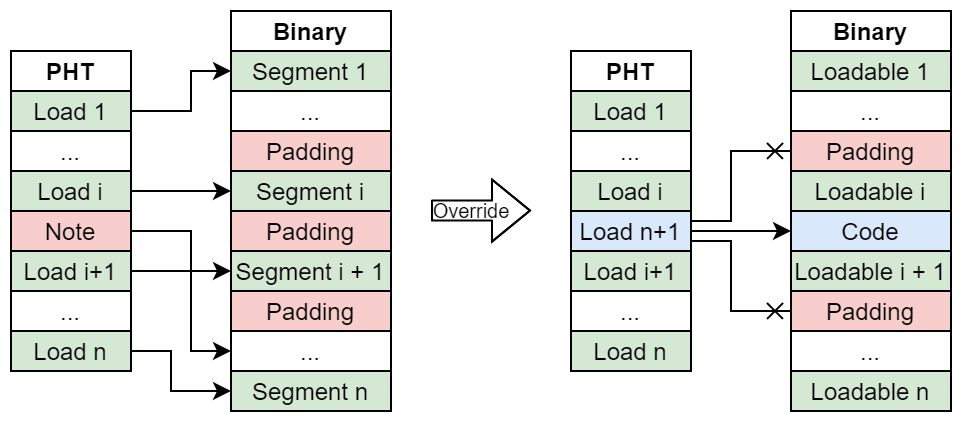

The following figure illustrates overwriting an existing PHT - entry such that it points to a segment - based code cave.

Segment - based Injection

This technique involves everything related to segments that is not already part of code cave - based injection . To be precise, the following subtechniques can be formed:

- Overwrite an existing PHT - entry and overwrite an existing memory region. This is an abstraction of overwriting an existing PHT - entry such that it points to a segment - based code cave. Of course the PHT - entry should point to the overwritten memory, which can be a segment that is not part of the process image or something else.

- Overwrite an existing PHT - entry and insert new memory to be interpreted as a segment. Inserting new memory will result in problems related to cross - references described in Code Injection . Also this will result in a “dead” memory region, because the memory region the overwritten PHT - entry was referencing is not interpreted as a segment anymore.

- Insert a new PHT - entry and overwrite an existing memory region. This is again an abstraction of a code cave - based injection technique, but now arbitrary memory can be interpreted as a segment (notice that the memory region we overwrite is not limited to memory regions between loadable segments as in Code - Cave - based Injection ). Although it can happen that two PHT - entries reference the same memory region. Again note that inserting a new PHT - entry may invalidate cross - references.

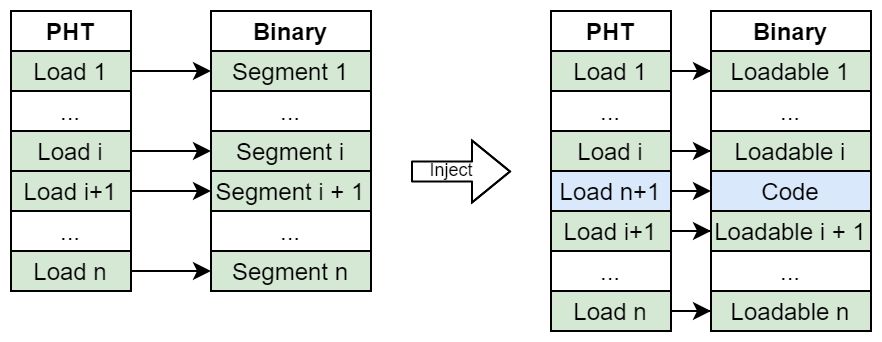

- Finally one can insert a new PHT - entry and a new memory region. As long as one can manage validating cross - references, this technique is the least intrusive one and is even reversible.

The following figure depicts inserting a completely new segment:

Thinking back to using two parsers

, we can see that the “mixed” techniques are problematic. To be precise, after calling rawelf_injection, LIEF will cause a segmentation fault during its parsing phase. It might be related to the fact that both “mixed” techniques result in some form of “dead” memory, i.e. either a “dead” PHT - entry or a “dead” memory region. A solution is to avoid reparsing, i.e. call rawelf_injection independently from LIEF.

Code Execution

Making already injected code executable is key to seeing any signs of life of our code. Technically speaking, there is a plethora of ways to make code executable, but most of them are highly platform - dependent. Thus we try to focus on the most abstract methods to archive code execution.

LIEF fully supports all following approaches, which prevents compatibility issues between the two parsers.

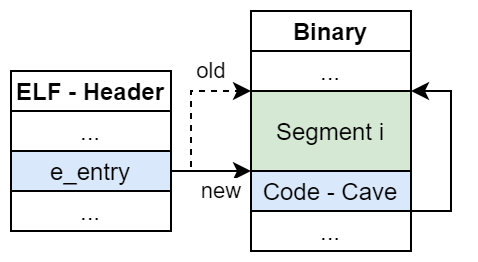

Entry Point

The most natural approach is to overwrite the entry point address e_entry located in the ELF - header. However, it might be unclear what to write into e_entry at the first glance. e_entry is a virtual address pointing to the first instruction executed after the OS/dynamic linker is done setting up the execution environment. As all code injection techniques discussed above work with file offsets, there needs to be a translation from file offet to virtual address. Fortunately, LIEF provides us with a function that does exactly that

vaddr = binary.offset_to_virtual_address(off)

Theoretically the conversion can be done manually aswell. For that assume that the injected code is part of a loadable segment (of type Elf64_Phdr). Then

vaddr = (off - seg.p_offset) + seg.p_vaddr

Intuition behind that is that the relative offset of a structure to the beginning of the segment that contains the structure will remain the same, regardless of whether we are in the process image or in the file. Note that this conversion might not work in general.

The following picture shows the general idea of this technique:

.dynsym - based Injection

Another idea to make code executable would be to define a symbol such that it points to the injected code. This technique is dependent on the Dynamic Linker, because the dynamic linker determines how a symbol is resolved at runtime. We would need the following assumptions:

- Dynamic Linker will not resolve a symbol, if there is already a non - zero definition in .dynsym, and will use that existing definition.

- Target binary uses Dynamic Linking.

- .dynamic neither contains an entry with tag

DT_BIND_NOWnor any other platform - dependent entry that enforces non - lazy binding. Also there must not be an entry with tagDT_FLAGSand valueDF_BIND_NOW. This is rather nice to have than necessary, because lazy binding allows for injected code to be executed before a symbol is resolved, thus leaving a time window, in which symbol resolution can be manipulated.

This time we are out of luck though. At least one of the above assumptions does not hold on our target platform and thus this technique is not applicable! If we were to manipulate relocations, we might be able to get a similar technique to work. Although it would not require .dynsym.

The Tradegy of Lazy Binding

For this section we assume that we are looking at an Android OS (e.g. 12) on an ARM64 (i.e. AARCH64) architecture. For these platform specifications I want to explain that the dynamic linker always uses BIND_NOW, i.e. non - lazy binding!

Lets remember that, if we execute a binary (e.g. using execve), the kernel will load the binary into memory. According to AOSP

, we can derive the following call stack:

| Order | Function Call | Line |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | syscall(execve, argv, envp) | - |

| 2. | do_execve(getname(filename), argv, envp) | line |

| 3. | do_execveat_common(AT_FDCWD, filename, argv, envp, 0) | line |

| 4. | bprm_execve(bprm, fd, filename, flags) | line |

| 5. | exec_binprm(bprm) | line |

| 6. | search_binary_handler(bprm) | line |

| 7. | fmt->load_binary(bprm) | line |

In the file common/fs/binfmt_elf.c

we can find the corresponding binary format that is registering load_elf_binary

as the function that is called last in the call stack. Investigating that function leads us to the conclusion that the kernel may handle loading the binary. Also we can see that if the program to be executed uses an interpreter, i.e. there is a segment of type PT_INTERP, then the kernel will set the entry point to the entry point of the interpreter

and start a thread at this entry point

.

This brings us to the dynamic linker, whose “nice” entry point is linker_main

. Of course we assume that we are looking at a binary that has at least one DT_NEEDED - entry in .dynamic. This will trigger a call to the function find_libraries

. This function tries to load all dynamic dependencies in a very complex way. Eventually it will call soinfo::link_image

with a lookup list containing descriptions of shared libraries to consider while linking:

if (!si->link_image(lookup_list, local_group_root, link_extinfo, &relro_fd_offset) ||

!get_cfi_shadow()->AfterLoad(si, solist_get_head())) {

return false;

}

Within soinfo::link_image, there is a sneaky call to relocate

:

if (!relocate(lookup_list)) {

return false;

}

We know that the first .plt - entry will lookup symbols, if the corresponding functions are called for the first time, in case of lazy binding. This means that we now expect corresponding relocations to take place s.t. .got.plt (according to this

, .got.plt holds symbol addresses used by .plt - entries) eventually contains all function addresses before the program gets in control. Thus we will look for R_AARCH64_JUMP_SLOT relocation types. Assuming the dynamic linker is compiled with USE_RELA, it will run

if (!plain_relocate<RelocMode::JumpTable>(relocator, plt_rela_, plt_rela_count_)) {

return false;

}

Following the one-liners we will wind up in process_relocation_impl

. As we are assuming that our relocation type of interest is R_AARCH64_JUMP_SLOT, we get that its r_sym refers to the corresponding .dynsym - entry and is thus not 0. This will result in an r_sym == 0 - check

to be false, which triggers a symbol lookup in the corresponding else:

if (!lookup_symbol<IsGeneral>(relocator, r_sym, sym_name, &found_in, &sym)) return false;

(btw. the relocator contains lookup_list).

Again following the control flow will reveal a call to soinfo_do_lookup

:

... soinfo_do_lookup(sym_name, vi, &local_found_in, relocator.lookup_list);

which, after following one - liners again, brings us to a function called soinfo_do_lookup_impl

. This function will resolve a given symbol by name utilising the hash sections and symbol versioning. Eventually, it returns an instance of Elf64_Sym that is forwarded all the way back to process_relocation_impl. It will be used to compute the correct address of the symbol via

ElfW(Addr) resolve_symbol_address(const ElfW(Sym)* s) const {

if (ELF_ST_TYPE(s->st_info) == STT_GNU_IFUNC) {

return call_ifunc_resolver(s->st_value + load_bias);

}

return static_cast<ElfW(Addr)>(s->st_value + load_bias);

}

As most symbols are of type STT_FUNC, we just consider the second return statement.

Finally, the result of resolve_symbol_address(sym) is stored in sym_addr

and used in

if constexpr (IsGeneral || Mode == RelocMode::JumpTable) {

if (r_type == R_GENERIC_JUMP_SLOT) {

count_relocation_if<IsGeneral>(kRelocAbsolute);

const ElfW(Addr) result = sym_addr + get_addend_norel();

trace_reloc("RELO JMP_SLOT %16p <- %16p %s",

rel_target, reinterpret_cast<void*>(result), sym_name);

*static_cast<ElfW(Addr)*>(rel_target) = result;

return true;

}

}

This will write the address of the symbol into the corresponding .got.plt - entry.

All in all this happens at startup of a program. We started at execve and only considered dynamic linker code that is executed before the program gets in charge (i.e. before the dynamic linker returns from linker_main). Therefore the dynamic linker always uses BIND_NOW.

Symbol Hashing and LIEF

In order to quickly determine, whether a symbol is defined in an ELF - file, two sections can be utilised:

- .gnu.hash

- .hash

We will only focus on .gnu.hash, because it suffices for showcasing the problem.

From the previous section we know that the dynamic linker performs a symbol lookup via soinfo_do_lookup_impl

. To be precise, it will iterate over all libraries defined in lookup_list and use the Bloom filter in .gnu.hash to check whether a symbol is defined in an ELF - file or not. If the Bloom filter “says no”, the symbol is not defined in that ELF - file with probability assumed to be 100%. If the Bloom filter “says probably yes”, then further checks are needed to identify whether the symbol is really defined in that ELF - file (for those interested, see this

).

This implies that there needs to be an entry in .gnu.hash in order for the dynamic linker to take a corresponding symbol definition into account. Unfortunately, LIEF does not create a new entry in .gnu.hash upon adding a new symbol to .dynsym. Neither does rawelf_injection, as it was designed according to System V gABI, which does not even mention .gnu.hash. Therefore overwriting an existing symbol in .dynsym using rawelf_injection will also not create/overwrite a .gnu.hash - entry. This leaves us with overwriting symbols, whose symbol names are already defined in .gnu.hash of the ELF - file we are manipulating. Thus we cannot overwrite symbols that are defined in other shared object files unless we manipulate the respective libraries. Lets assume we have a symbol to overwrite, then there is a limitation to what the corresponding .dynsym - entry must look like. Notice that in soinfo_do_lookup_impl

there is a call to is_symbol_global_and_defined

:

inline bool is_symbol_global_and_defined(const soinfo* si, const ElfW(Sym)* s) {

if (__predict_true(ELF_ST_BIND(s->st_info) == STB_GLOBAL ||

ELF_ST_BIND(s->st_info) == STB_WEAK)) {

return s->st_shndx != SHN_UNDEF;

} else if (__predict_false(ELF_ST_BIND(s->st_info) != STB_LOCAL)) {

DL_WARN("Warning: unexpected ST_BIND value: %d for \"%s\" in \"%s\" (ignoring)",

ELF_ST_BIND(s->st_info), si->get_string(s->st_name), si->get_realpath());

}

return false;

}

This function has to return true in order for our symbol to be returned by soinfo_do_lookup_impl. Therefore, its binding must ensure that the symbol is globally available, i.e. either STB_GLOBAL or STB_WEAK, and the symbol has to be defined in relation to some section, whose index is not 0. (We have not talked about symbol version checks

yet that introduce further complexity if there is a section of type SHT_VERSYM. Note that check_symbol_version

also has to return true for the symbol resolution to succeed.)

Thus manipulating .dynsym of an ELF - file is limited to the symbols that have a corresponding .gnu.hash - entry.

Combining the facts that the dynamic linker defaults to BIND_NOW and uses hash tables like .gnu.hash and .hash, overwriting a .dynsym - entry will be ignored and changes in e.g. .got.plt will be overwritten, if there is no corresponding hash entry. Having lazy - binding would relax the situation a bit, as the symbol lookup would be delayed as much as possible, allowing further manipulations at runtime. BIND_NOW enforces the existence of a hash table entry at startup in order for .dynsym - based injection to work. Alternatively we could overwrite a relocation entry of type R_AARCH64_JUMP_SLOT, which does not seem to require any other changes than in .rel(a).plt.

.dynamic - based Injection

Finally, the most common technique is described. This approach requires dynamic linking, i.e. if the target binary is statically linked and there is no .dynamic - section, then this technique will not work. Also we assume that all inserted .dynamic - entries have the tag DT_NEEDED to allow loading arbitrary shared object files. The corresponding d_val is an offset into .dynstr.

The following subtechniques can be derived:

- Inserting a new .dynamic - entry into .dynamic and a new string into .dynstr. Like in segment - based injection, this is the least intrusive and only reversible technique and is supported by LIEF. One issue is that it requires new memory to be inserted. E.g. on an ARM64 architecture with Android 12 (API level 31) and a NDK r23b build of a “Hello World” - application, .dynamic is located between .plt and .got/.got.plt. Therefore, inserting new memory will invalidate cross - references.

- Similar to the above, overwriting an existing .dynamic - entry and inserting a new string results in a recomputation of all patchable references.

- Inserting a new .dynamic - entry with a chosen string offset as

d_valrequires to find a “suitable” substring in .dynstr. Thinking of Frida, this substring should be of the form “substring.so”. This allows the use of configuration files for frida-gadget.so. - At last we can overwrite an existing .dynamic - entry and use a “suitable” substring. Notice that some compilers (like e.g. gcc) like to generate a .dynamic - entry with tag

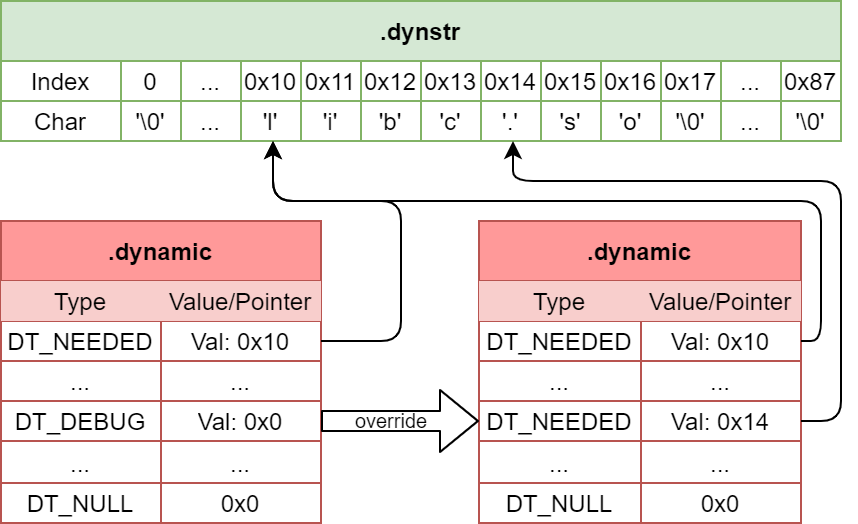

DT_DEBUG. Its value is application - dependent. As this is marked as optional in System V gABI, it can be overwritten. If the application needs this .dynamic - entry, then you will have to restore this entry in the initialisation function of your shared object file.

One main concern is that LIEF does not support using substrings. If LIEF sees that a .dynamic - entry with tag DT_NEEDED is inserted, it will insert a new string. Thus rawelf_injection will be used for substring - related techniques. Also overwriting an existing .dynamic - entry and inserting a new string is implemented by using the sequence

binary.remove(binary.dynamic_entries[index])

binary.add_library(string)

If the .dynamic - entry indexed by index is e.g. a DT_NEEDED - entry, then LIEF will also remove the corresponding string from .dynstr. One must be cautious when removing .dynamic - entries with LIEF.

Lets consider a figure that describes the last subtechnique:

Applicability

Having seen all of those techniques, we should summarise what techniques are usable and under which circumstances. For that, please see the following table. The test environment is always on AMR64 and Android 12 (API level 31). Notice that we consider LIEF as a black - box and assume its correctness to be given.

| Technique | Subtype | Usable | Constraints & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insert Memory | - | Yes | adrp, invalid cross - references, inserting memory after loadable with p_filesz=0, permissions, overlapping loadables |

| Code Caves | Extension | Yes | segment permissions, adrp, overlapping loadables |

| PHT Insert | Yes | Insert Memory issues, possibly order of loadables, … | |

| PHT Overwrite | Yes | finding “suitable” PHT - entry, adrp because different p_memsz, possibly order of loadables, … | |

| Segments | Inject(PHT)+Inject(Memory) | Yes | None, unless LIEF messes up |

| Overwrite+Overwrite | Rather no | finding “suitable” PHT - entry, finding “suitable” segment, adrp because different p_memsz, possibly order of loadables | |

| Overwrite+Inject | Rather yes | Insert Memory issues, finding “suitable” PHT - entry, possibly order of loadables | |

| Inject+Overwrite | Rather no | Insert Memory issues, finding “suitable” segment, possibly order of loadables | |

| Entry Point | - | Yes | need virtual address |

| .dynsym | Insert Symbol | No | Dynamic Linker always uses BIND_NOW, need specific hash table entries |

| Overwrite Symbol | No | Insert Symbol issues | |

| .dynamic | Inject(.dynamic)+Inject(.dynstr) | Yes | None, unless LIEF messes up |

| Overwrite+Inject | Yes | None, unless LIEF messes up | |

| Inject+Substring | Yes | finding “suitable” substring | |

| Overwrite+Substring | Yes | finding “suitable” substring, finding “suitable” .dynamic - entry |

It is needless to say that overwriting vital structures like e.g. the ELF - header will completely break the binary. Always think about it twice when considering to overwrite something.

All in all we can see that most techniques work. I must emphasize that the above table is solely based on tests on a single platform for a single binary. Although theoretically correct, in practice many techniques can still fail due to bugs in the implementation on my side or deviations from specifications and standards on the vendor’s side. Also you should take the “Usable” - column with a grain of salt: it highly assumes that the user knows what he/she is doing. Blindly injecting memory will most likely result in segmentation faults.

Practical Examples

In this section we want to see whether these techniques can be used to make Frida work. Notice that for simplicity, we will only use .dynamic - based injection to get Frida to run. This is justified by the fact that writing shellcode that is able to either track down dlopen and thus libc or load a shared object file manually is non - trivial. To prove that other techniques work aswell I will provide shellcode that writes a plain “Hello World!” text to stdout and exits with code 42.

Experiment Setup

In order to test the library, one may go ahead and create an Android Virtual Device (AVD) with API level 31 or above to support aarch64 - binaries (i.e. ARM64). Then run the emulator, e.g. via console

emulator -avd Pixel_3_API_31

where emulator is a tool in the Android SDK. The name of the AVD may differ.

Then use adb to get a shell into the emulator using

adb shell

This assumes that there is only one emulator running. Otherwise you need to specify the avd or its debug port.

Finally, cross-compile a C program of your choice by utilising the Android NDK or take a binary that is a result of the Ahead-Of-Time step of ART. Either way you should end up with an ELF - file. When cross - compiling a C program, use

adb push /path/to/binary /local/data/tmp/binary

to get the binary into the emulator.

As the python library only runs on AMD64, you should apply the techniques before pushing the ELF - file to the emulator.

Hello World - Example

Lets use code cave - based injection. For simplicity, we assume that there is a code cave between loadable segments.

#import lief

from ElfInjection.Binary import ElfBinary

from ElfInjection.CodeInjector import ElfCodeInjector

from ElfInjection.Seekers.CodeCaveSeeker import *

def main():

# 0. Introduce artificial code cave

#binary = lief.parse('./libs/arm64-v8a/hello')

#binary.add(binary.get(lief.ELF.SEGMENT_TYPES.LOAD))

#binary.add(binary.get(lief.ELF.SEGMENT_TYPES.LOAD))

#binary.write('./libs/arm64-v8a/hello')

# 1. Setup variables

shellcode = (b'\x0e\xa9\x8c\xd2\x8e\x8d\xad\xf2\xee'

+ b'\r\xc4\xf2\xee\xea\xed\xf2O\x8e\x8d\xd2\x8f,'

+ b'\xa4\xf2O\x01\xc0\xf2\xee?\xbf\xa9 \x00\x80'

+ b'\xd2\xe1\x03\x00\x91\xa2\x01\x80\xd2\x08\x08'

+ b'\x80\xd2\x01\x00\x00\xd4@\x05\x80\xd2\xa8\x0b'

+ b'\x80\xd2\x01\x00\x00\xd4')

# 2. Get the binary

binary = ElfBinary('./libs/arm64-v8a/hello')

injector = ElfCodeInjector(binary)

# 3. Create cave seeker and search for caves of size

# at least 0x100

seeker = ElfSegmentSeeker(0x100)

caves = injector.findCodeCaves(seeker)

# 4. Find suitable code cave...

cave = caves[1]

# 5. Adjust a loadable segment. This should also be executable!

cave.size = len(shellcode)

sc, _ = injector.injectCodeCave(None, cave, shellcode)

# 6. Overwrite entry point to point to whereever shellcode is

old = injector.overwriteEntryPoint(sc.vaddr)

# 7. Store to file

binary.store('./libs/arm64-v8a/tmp')

if (__name__ == '__main__'):

main()

The above code will search for a code cave that is at least 0x100 bytes in size. Then it will select the second match, fill the cave with shellcode and set the entry point to point to the shellcode. Notice that the code cave will be appended to an executable segment. The target is the same binary as in the next example.

Also notice that we need to artificially introduce two loadable, executable segments in order to find a code cave. If such an action is necessary to perform code cave based injection, you must reconsider whether code cave based injection is the correct choice.

.dynamic - Injection Example

Finally, for .dynamic - based injection please consider the following code:

import lief

from ElfInjection.Binary import ElfBinary

from ElfInjection.CodeInjector import ElfCodeInjector

from ElfInjection.Manipulators.DynamicManipulator import ElfDynamicOverwriter

from ElfInjection.Manipulators.StringManipulator import ElfStringFinder

def main():

# 1. Get the binary

binary = ElfBinary('./libs/arm64-v8a/hello')

injector = ElfCodeInjector(binary)

# 2. Create overwriter

dyn_overwriter = ElfDynamicOverwriter(

tag=lief.ELF.DYNAMIC_TAGS.NEEDED,

value=0,

index=6

)

# 3. Create string finder

str_finder = ElfStringFinder()

# 4. Overwrite .dynamic entry with substring

dyn_info = injector.injectDynamic(

str_finder,

dyn_overwriter

)

# 5. Store to file

binary.store('./libs/arm64-v8a/tmp')

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Because we are using an ElfStringFinder, there is no user - supplied string injected into .dynstr. Note that the user is responsible for providing the requested shared object file, e.g. by setting LD_LIBRARY_PATH. We are manipulating the following program

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

char *text = "Hello World!\n";

while (1) {

write(1, text, strlen(text));

sleep(1);

}

}

compiled on AMD64, Ubuntu 20.04.1 LTS with Android NDK r23b

ndk-build

Investigating .dynamic yields:

readelf --wide --dynamic manipulated.bin

...

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libc.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libm.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libstdc++.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libdl.so]

0x000000000000001e (FLAGS) BIND_NOW

0x000000006ffffffb (FLAGS_1) Flags: NOW PIE

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [c.so]

0x0000000000000007 (RELA) 0x1490

...

To see Frida in action, we first need to set the gadget’s bind address to an IP we can connect to (i.e. not localhost):

{

"interaction": {

"type": "listen",

"address": "<IP>",

"port": 27042,

"on_port_conflict": "fail",

"on_load": "wait"

}

}

Name this file “c.config.so”.

Now run the following in separate shells to see Frida in action. The first shell should run something like this, setting up the test program.

mv frida-gadget.so c.so

LD_LIBRARY_PATH=. ./manipulated.bin

And the second shell should do the tracing:

frida-trace -H <IP>:27042 -n "Gadget" -i "write"

Sources

- https://cs.android.com/android

- https://frida.re

- https://frida.re/docs/gadget/

- https://github.com/fkie-cad/ELFbin

- https://github.com/frida/frida/releases

- https://github.com/lief-project/LIEF

- https://gitlab.com/x86-psABIs/x86-64-ABI

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/ptrace.2.html

- https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/ld.so.8.html

- http://www.sco.com/developers/gabi/latest/contents.html

- http://www.sco.com/developers/gabi/latest/ch4.reloc.html